ON LIVING UP THE HOLLER

By Alanna Autler

In June of 2012, the postgrad winds scattered my beautiful, brilliant friends to the throbbing metropolises of America — places with public transit and restaurants that only sell salad, supposed paradises where yoga studios beckon from every other concrete corner.

I remember (with a pang of jealousy) hearing the early trials of many of my peers — lost in a grand prix of happy hours and dating apps and the idea that one must shine in an infinite sea of over-achievers.

But let the record show — that is not my story. Mine, rather, starts in a holler.

Maybe you don’t know what a holler is. Don’t worry; four years ago, I certainly did not either. A person once told me that a holler is an Appalachian derivation of “hollow” — land between two mountains where people generally live.

That, or the word could also mean the easiest way to communicate from one side of the hollow to another: to holler. That makes far more sense, in my opinion.

But this was just one of the many things I learned upon arriving in my new home.

A week after graduation, I moved to Dunbar, West Virginia — a dusty town eight miles west of the state capital — to work at a TV station. My apartment sat off a curvy road, etched in the mountains.

It became very clear very quickly that I was not in my college town anymore.

“At first, I was too engrossed in my new job, eating epic biscuits and/or taking in the natural beauty to dwell on anything beyond the next five minutes. But the loneliness eventually encroached.”

The only word I can find to describe that apartment complex is haphazard. Peeling wallpaper covered some parts, but not all. The stairway reeked of cabbage. Someone broke into my unit within six months and stole my shit.

The apartment was adjacent to our very own holler, which became my retreat every day before dawn. At that time, the town had no real gyms. (Say it with me: “First. World. Problems.”) So for exercise, I sprinted up and down that holler, passing the same houses three, four, five times as the world awoke, all the while blasting Top 40 hits that had played at sorority formals just weeks earlier. White noise in my otherwise silent life.

I answered to no one. Six months earlier, I had ended a very serious, long relationship. Without this attachment, I immersed myself in a place where I knew no one and no one knew me. It was liberating.

At first, I was too engrossed in my new job, eating epic biscuits and/or taking in the natural beauty to dwell on anything beyond the next five minutes. But the loneliness eventually encroached.

She seeped into my life ever so slowly. In that great, wide wilderness, she waded through every nameless tributary and zeroed in on the faraway fortress I had created to reinvent myself.

Loneliness will always find you. And when she does, you cannot hide.

When I say I had no friends for several months, that is not an exaggeration. It’s not like my childhood friend’s cousin happened to live off the next subway stop, and I just decided we didn’t click. I literally had no friends in my town. So my early triumphs and failures were digested in the same fashion: I went home, sat on my couch and ate salad out of a bag.

A fog descended. I carried her constantly. Through the mountains — always through the mountains — as I steered a ratchet PT Cruiser that served as a news car and stunk of spoiled milk (someone had actually left milk in it). She joined me in the empty Kroger I frequented at 1 a.m. because I worked the night shift, and even in the mall, which seemed trapped in some strange time capsule (When was the last time you shopped at Deb?).

“That freedom I once held so dear became a captor.”

I was alone, and the silence was searing. As a one-man-band reporter, I shot, edited and wrote all my stories, driving myself to faraway towns every day. There was no ironic juxtaposition of feeling singular among the teeming masses. In my case, I was feeling lonely because there was often no one around. Many stories brought me to vacuous coalfields, gutted by layoffs. On really, really bad days, I'd assume the fetal position at the foot of my bed and cry so loudly I sounded like a dying animal.

That freedom I once held so dear became a captor. I felt like if I flung myself off a mountain, no one would see nor notice. (Edit: My managers would have noticed upon missing deadline.)

“You chose this,” I told my reflections in various gas station bathroom mirrors.

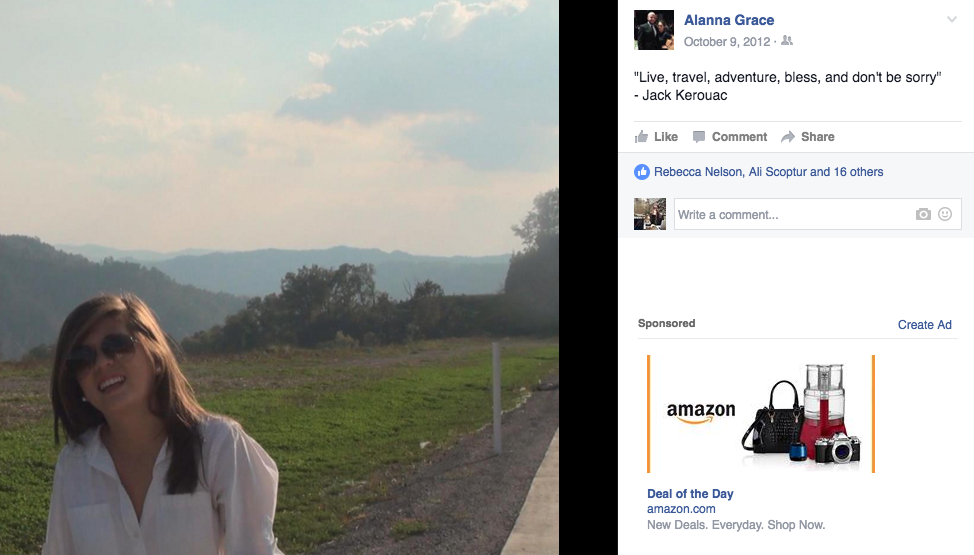

In this picture, I am shooting my first real enterprise story. It was my first time in Mingo County — a beautiful place riddled with corruption — which would become the bedrock of my time in West Virginia. I parked the car on the side of King Coal Highway and stepped out. It was October and the air was still humid. I set my camera on a self-timer and stood near the crevice between the pavement and the earth. This — I thought — this is what I’ll look at when I’m older and wiser and saner.

Little did I know, I had already embarked on the greatest adventure of my life. And I needed to go it alone.

I'm not sure I was a good person when I arrived. Without distractions, I had a lot of room to think. To sit with my mistakes or my guilt, whatever seized me that day. To replay things I had uttered to friends or loved ones carelessly. To navigate the type of woman I was becoming.

And when I was done thinking — once again reassured of my place within this world — I had no choice but to think some more.

My only companion was Loneliness, and she saved me.

I guess what I’m trying to say is wherever we are — a coastal metropolis or an Appalachian valley — we get lonely. And when we do, it helps to understand why.

It was in loneliness that I forced myself to contemplate my character, to write furiously, to go on dates, to find friends. Eventually it worked. It’s that simple. We are the only people who can fill our own voids.

Today I live elsewhere, adorned with a slew of adjectives: happy, fulfilled, challenged. I moved to another city — this one a little bigger. But every now and then, I still catch myself looking for those hollers.

I wonder if they're looking for me, too.

Alanna Autler works as a reporter in Nashville, Tennessee, where she continues to eat biscuits.